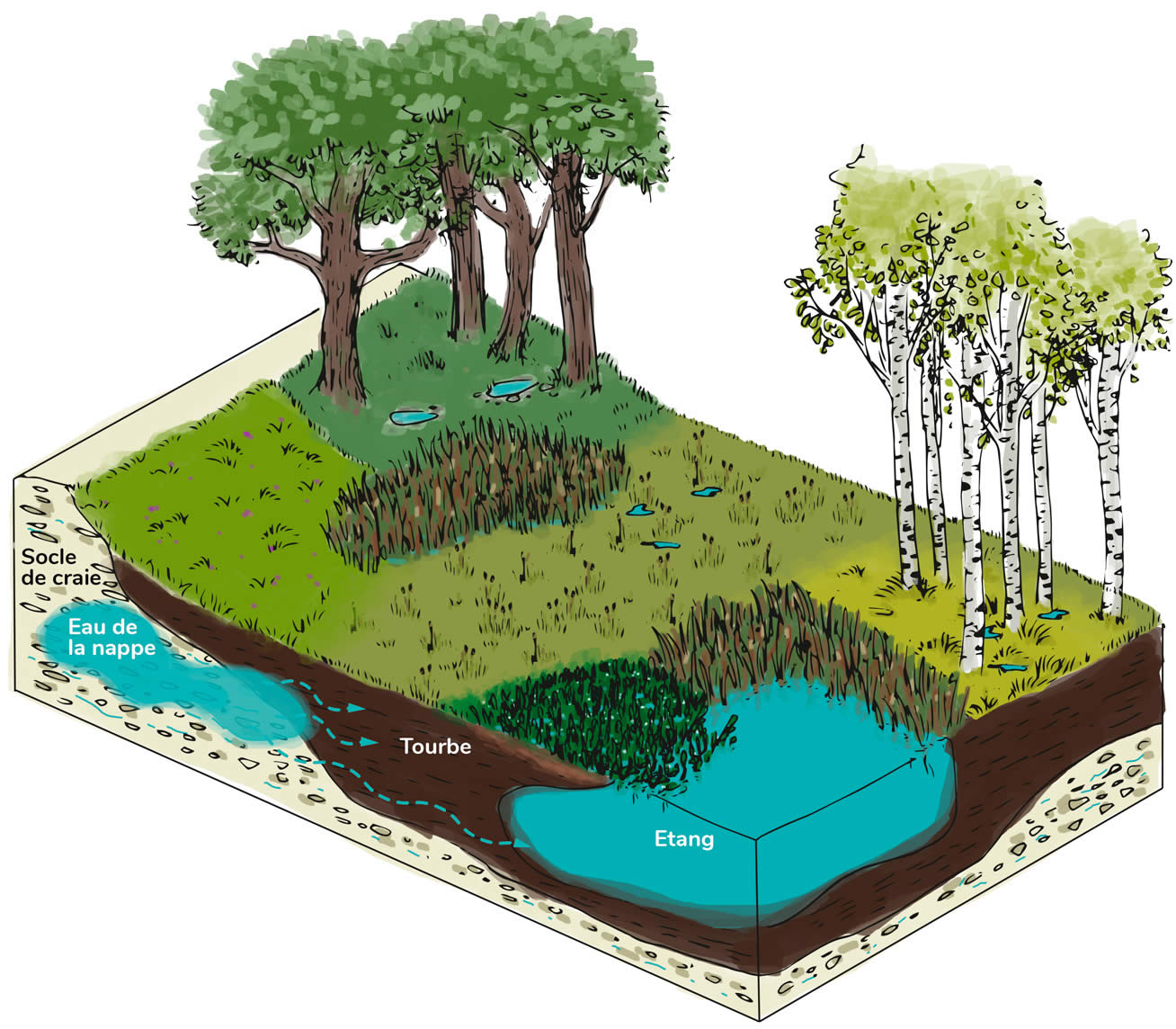

Location of six target natural habitats within an alkaline fen

The clickable image below is a simplified and theoretical representation of an alkaline fen. It only takes into account the six LIFE Anthropofens selected habitats. In reality, alkaline fens can be made up of other habitats, and the water system may work differently. These fens are generally interlinked with other types of wetland.

There are six selected habitats :

| Natura 2000 code | Habitat name |

Common name in northern France and Wallonia |

| 6410 | Molinia meadows on calcareous, peaty or clayey-silt-laden soils | Purple moor-grass and rush pasture |

| 7140 | Transition mires and quaking bogs | Transition mires |

| 7210* |

Calcareous fens with Cladium mariscus and species of the Caricion davallianae |

Calcium-rich fen dominated by great fen sedge |

| 7230 | Alkaline fens | Alkaline fens |

| 91D0* | Bog woodland | Bog woodland |

| 91E0* |

Alluvial forests Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior (Alno-Padion, Alnion incanae, Salicion albae) |

Riverine [Fraxinus] - [Alnus] woodland, wet at high but not at low water |

Molinia meadows on peaty limestone or silty clay soils (6410) :

Purple moor-grass (Molinia caerulea) meadows are an agropastoral habitat found at the edges of fens. This is one of the least wet habitats selected in the programme. In this type of poor wetland purple moor-grass predominates, along with a number of other species depending on the type of soil and water supply. This explains why so many variations of this habitat have been described.

Even though purple moor-grass meadows tend to develop in dried fens at the expense of more peaty habitats, their numbers are still in steep decline on a Europe-wide scale, especially in France and Belgium. These wet meadows have been greatly affected by changes in farming techniques, either because farming has ceased (with an end to extensive livestock raising and scything for hay), has intensified (with drainage, fertilisers, etc.) or due to changes in land use (poplar plantations, unauthorised hut building, etc.).

Maintaining this habitat is conditioned by agropastoral practices, which will help to preserve this type of open environment, while maintaining extensive farming practices without draining or fertilising wetlands.

Transition mires and quaking bogs (7140) :

Transition mires are remarkable pioneers. Their development points to an active turfigenous dynamic where aquatic habitats and land habitats meet. Transition mires consist of plants that develop into a floating (quaking) raft with varying degrees of contact with the bottom of a body of water. The main plants to be found in them are bottle sedge (Carex rostrata), woollyfruit sedge (Carex lasiocarpa), bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata) and purple marshlocks (Comarum palustre).

Transition mires are located in the most dynamic parts of a fen, where the water supply is better and "mosaics" can be formed with alkaline fens as a result of variations in microtopography.

This is a natural habitat that needs no specific management when it is active in a productive fen. In some situations, the most soil-rich quaking bogs can be periodically cut down to prevent colonisation by wood elements and to block the spontaneous development of vegetation. This dynamic can also triggered by turf cutting (removing the top part of the soil) or rejuvenating local bodies of water.

Calcareous fens with Cladium mariscus and species of the Caricion davallianae (7210*) :

Great fen-sedge (Cladium mariscus) is a remarkable form of vegetation for its density and almost impenetrable substance. Great fen-sedge calcareous fens appear as dense fields with a height of about 1.5 metres. A few companion species are thinly scattered here and there, providing significant variations in habitats.

The sedge may develop around ponds or in a mosaic pattern with alkaline fen vegetation. Great fen-sedge seems to tolerate wide variations in water levels from one year to the next. It has a strong capacity for colonisation (with creeping rhizomes).

Despite its uniform character, the habitat is very important for fauna. The thick plant litter is home to many insects and molluscs, such as the narrow-mouthed whorl snail (Vertigo angustior). The least dense sectors with a groundswell of water are the hunting ground of one of France's largest spiders, Dolomedes plantarius. A few birds also make their nests in calcareous fens, including the Savi's warbler (Locustella luscinioides) and the western marsh harrier (Circus aeruginosus).

Alkaline fens (7230) :

Alkaline fens are at the centre of a peatland area, where the soil is constantly water-logged, so that peat can form.

The list of plants living there includes the most endangered peatland species. The main species are the blunt-flowered rush (Juncus subnodulosus), the black bog-rush (Schoenus nigricans) and many small sedges, such as the yellow sedge (Carex lepidocarpa), tawny sedge (Carex hostiana), as well as rare mosses, such as the hook moss (Scorpidium cossoni).

The habitat can also be found with another form of vegetation, which deviates from the norm in terms of shape and floral composition. The predominant flora in these "low marshes with tall grasses" are common reeds (Phragmites australis), marsh fern (Thelypteris palustris) and milk parsley (Thysselinum palustre). These types of plants develop on richer soils than in the first kind of fen. The two kinds of habitat may be home to fen orchids (Liparis loeselii), a rare orchid that is in rapid decline in Europe.

Conserving alkaline fens mainly involves maintaining water quality and levels, so that enough water reaches the soil surface.

Bog woodland (91D0*) :

Bog woodland is rare in Hauts-de-France and Wallonia. Its development requires specific conditions, particularly water that is low in limestone and nutrients. Unlike other forms of afforestation occurring after a fen has dried out, this kind of habitat requires a good supply of water and near-permanent saturation.

In the LIFE sites, the habitat features alder and birch groves with peat moss. Common species include the black alder (Alnus glutinosa), the downy birch (Betula pubescens) and mosses from the sphagnum genus, as well as a wide range of fern species.

The habitat is best left to evolve freely. It should be allowed to mature over time with water levels maintained.

Alluvial forests with Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior (Alno-Padion, Alnion incanae, Salicion albae) (91E0*) :

The alluvial alder and birch forest with tall grasses is not strictly speaking peatland. It is a habitat located on the banks of a waterway and in alluvial plains on mineral soils that are less compact than the soils in fens. But a variation with organic peat soils can be found in fens in alluvial valleys. This a form of afforestation developing on the edge of active peat bogs. The habitats are of undeniable ecological interest.

The most important forests from an ecological point of view are those that are waterlogged for much of the year.

Tree growth and ageing are restricted by the water. This soon gives rise to a mature and fairly sparse forest where fallen trees create open spaces. In these newly formed clearings, peat and open marshland species can appear. The plants living in open environments can last over time along with the forest.

The most common trees in these forests are the black alder (Alnus glutinosa), the European ash (Fraxinus excelsior) and, less often, the European white elm (Ulmus laevis) and the bird cherry (Prunus padus).

As is the case for bog woodland, the importance of alluvial forests lies in their reaching maturity and in maintaining water levels. This is why these habitats should be left to evolve freely.